It’s no secret that the developer experience with the Solana toolchain isn’t great. A major reason is that Solana uses BPF, but instead of building directly on upstream eBPF, it maintains a custom sBPF backend, a fork of the Rust compiler, and an independent toolchain. As a result, every time there’s an improvement or upgrade from upstream, it takes significant effort to integrate those changes, and sometimes the divergence is so large that it’s no longer feasible at all.

While eBPF itself is highly constrained, being designed for use in the kernel and limited in ways sBPF isn’t, the Solana compiler is implemented with LLVM, the most widely used compiler framework, which supports many targets without those restrictions. In theory, LLVM is fully capable of enabling these features; if we can identify the right transformation passes and configure the compiler properly, it should just work!

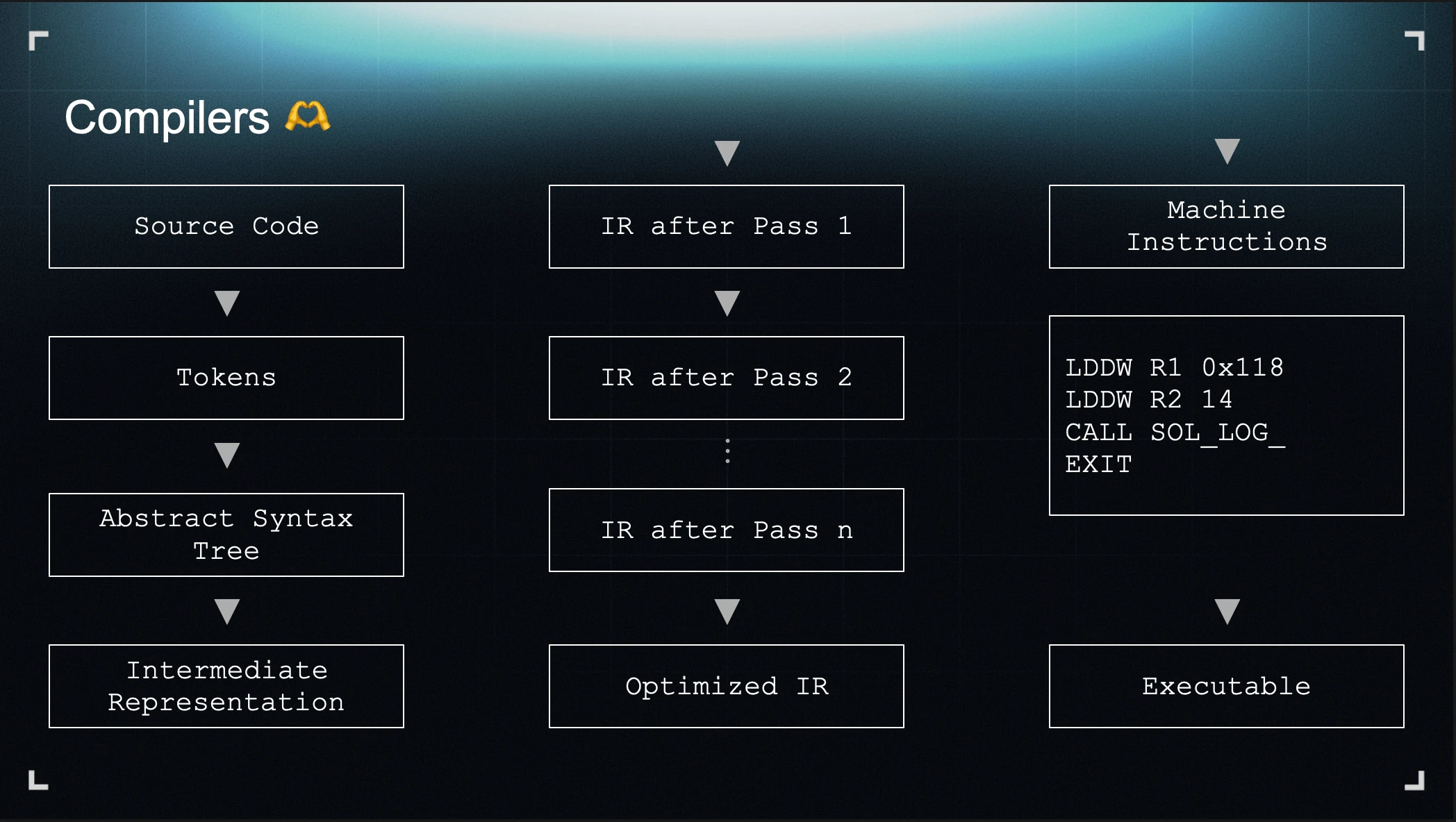

I’d like to take this opportunity to demystify compilers. They’re often treated as black boxes, but at the end of the day, they’re just software. A compiler takes your program’s source code as input, runs it through pipelines of transforms, and produces code that can run on your target hardware.

This is also what makes your programs portable. It’s the reason you can compile and run the same Rust program on a Windows computer, a MacBook, or even a Raspberry Pi. Toward the final stages of the compilation pipeline, the compiler starts emitting machine instructions tailored to your hardware. But machines still don’t understand those instructions directly. They only speak binary. So the compiler packages them into a bytecode format the machine can interpret and execute.

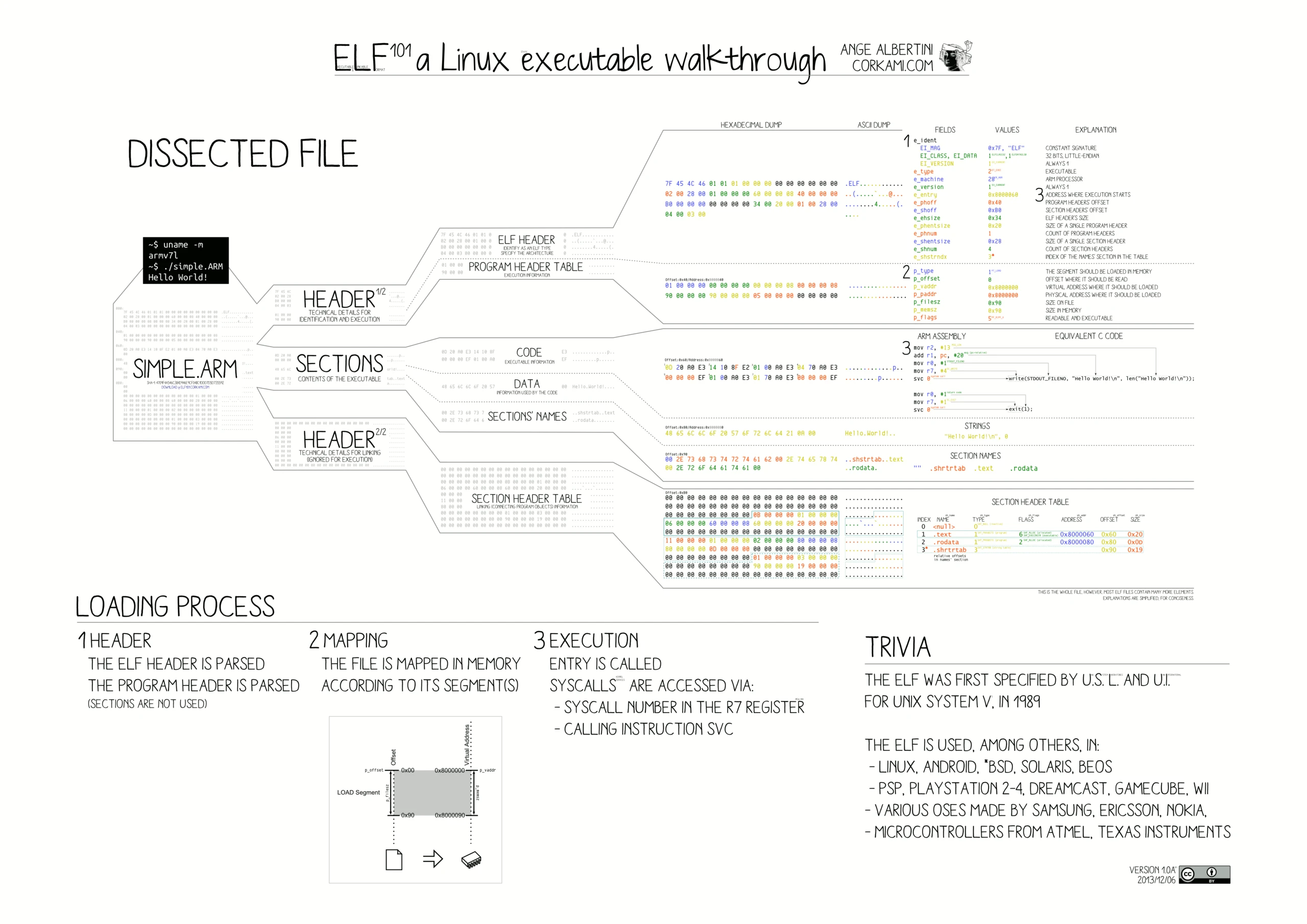

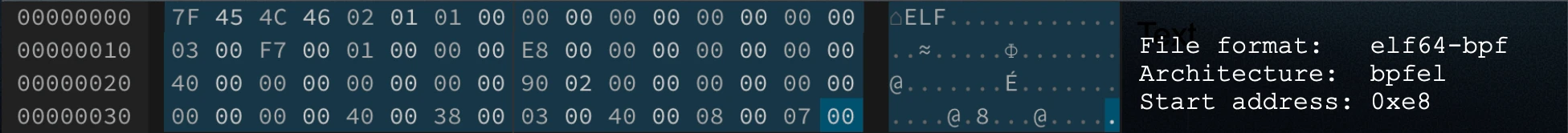

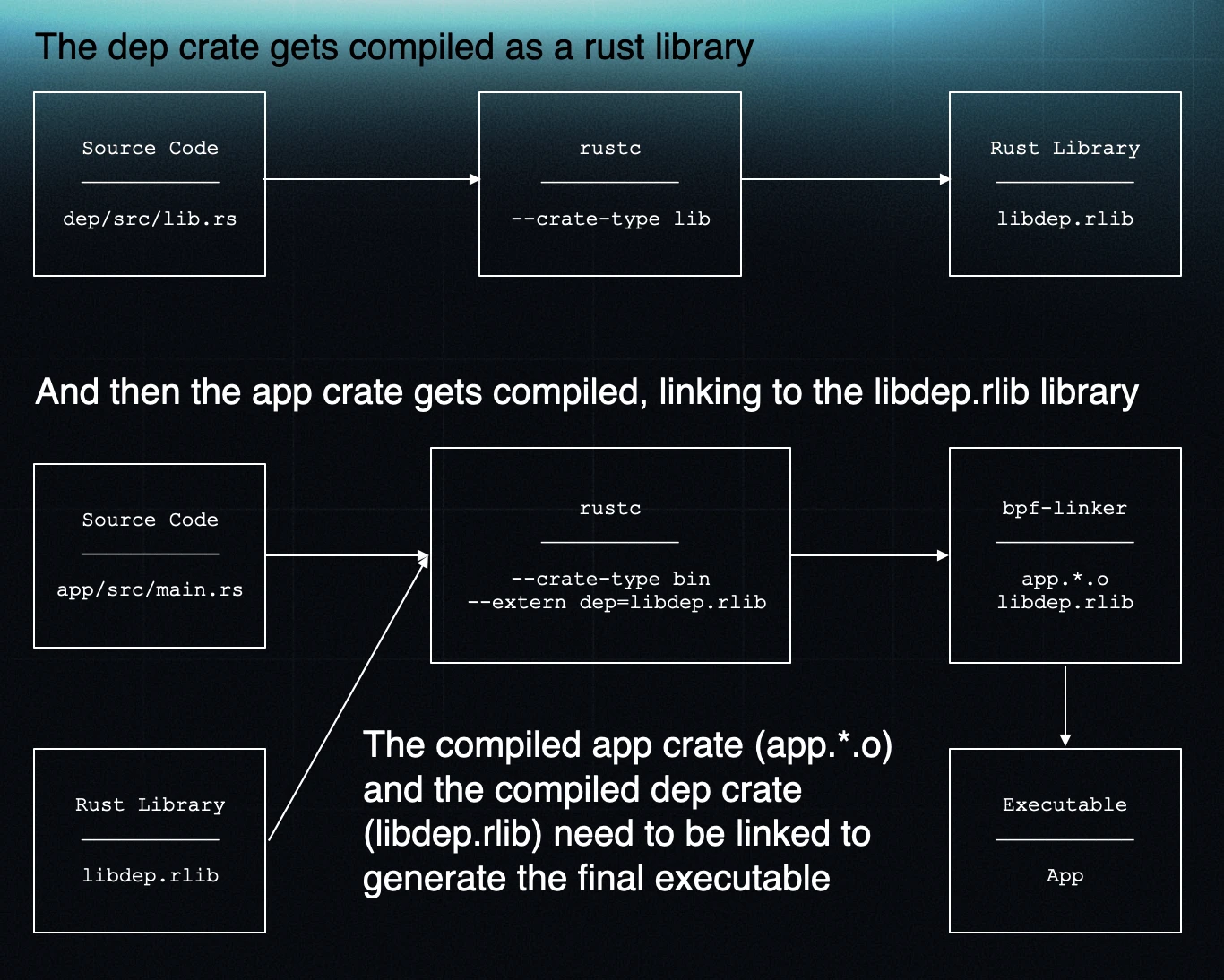

For BPF targets, the output uses the ELF format—short for Executable and Linkable File. An ELF file starts with a magic number (0x7F 45 4C 46), which corresponds to the characters “ELF” in the file header. Besides the ELF header, a program is composed of program headers and various sections that describe its structure and contents.

Let’s take a Solana program as an example. Dean did an excellent breakdown of the sBPF bytecode, which gives us a clear idea of the sections needed to compose a Solana program.

Just like any other ELF file, a Solana program begins with an ELF header. The ELF header describes key information about the binary, such as the target architecture, endianness, and the entry point address, which points to the first instruction that runs when the program starts executing.

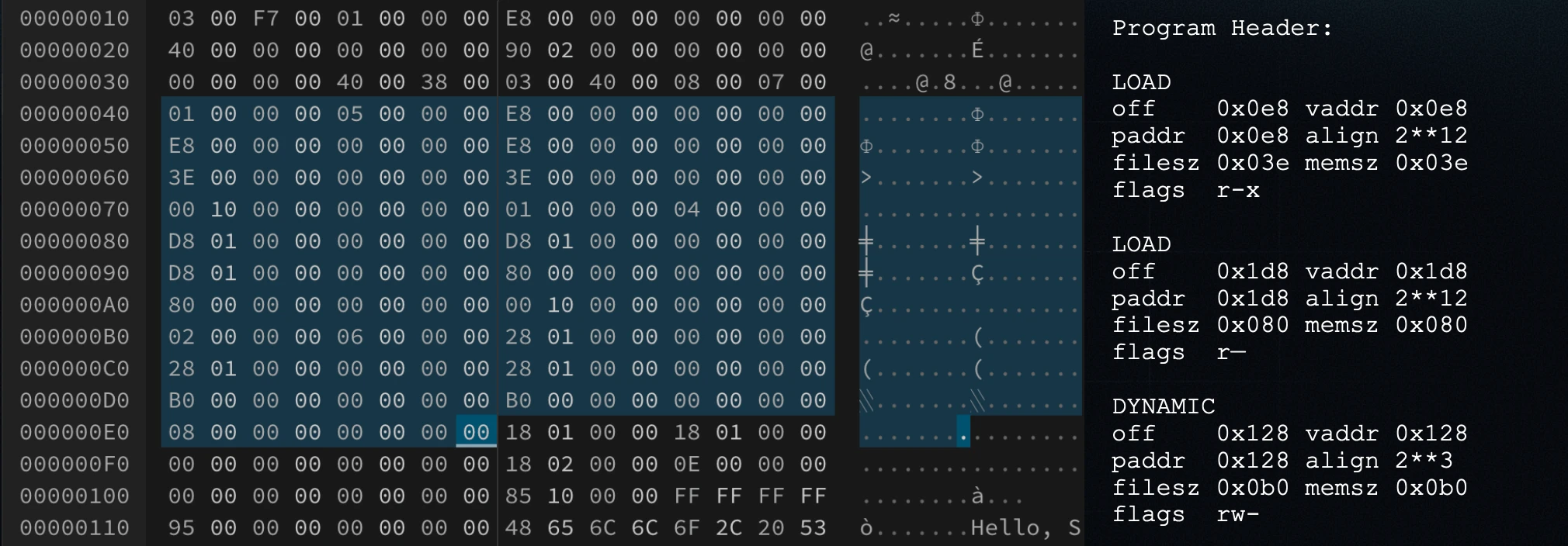

Next to the ELF header are the program headers. For dynamic programs, there are typically three: executable (r-x), read-only (r--), and dynamic (rw-). These headers describe each segment’s offset, alignment, and size in the binary.

For static programs, however, there’s no need to include any program headers, since there are no dynamic sections to jump to. Currently, the only feature that makes a Solana program “dynamic” is the use of syscalls because the Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) performs dynamic relocation for them. That’s why we’ve been pushing the direction of static syscalls: once syscalls are resolved statically, there’s no need to include program headers at all, allowing us to save these bytes.

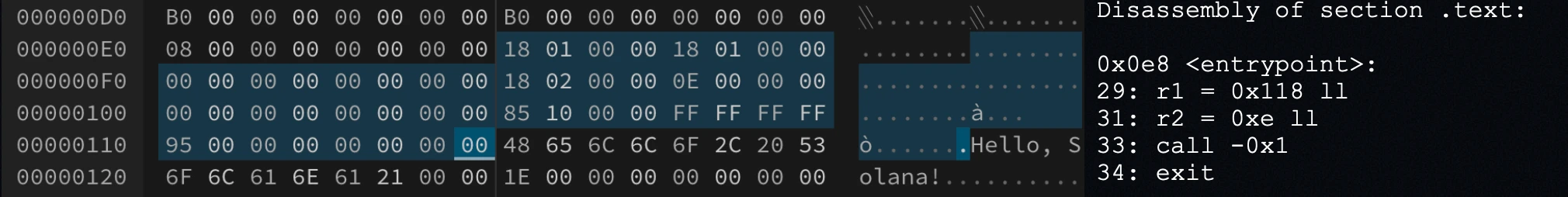

Following the program headers is the .text section, the part of the ELF that contains your program’s executable code. If you decode the bytes in this section, you’ll get the disassembly of your program, the actual machine instructions that will be executed by the virtual machine.

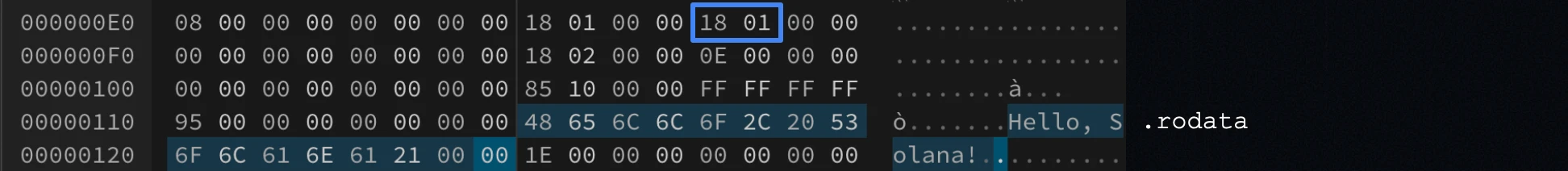

This program logs “Hello, Solana!”, and that string literal is stored in the .rodata section, which holds read-only data. In the .text section, one of the load instructions loads the string’s address into the r1 register, which is then used by the sol_log_ syscall to print the message at runtime.

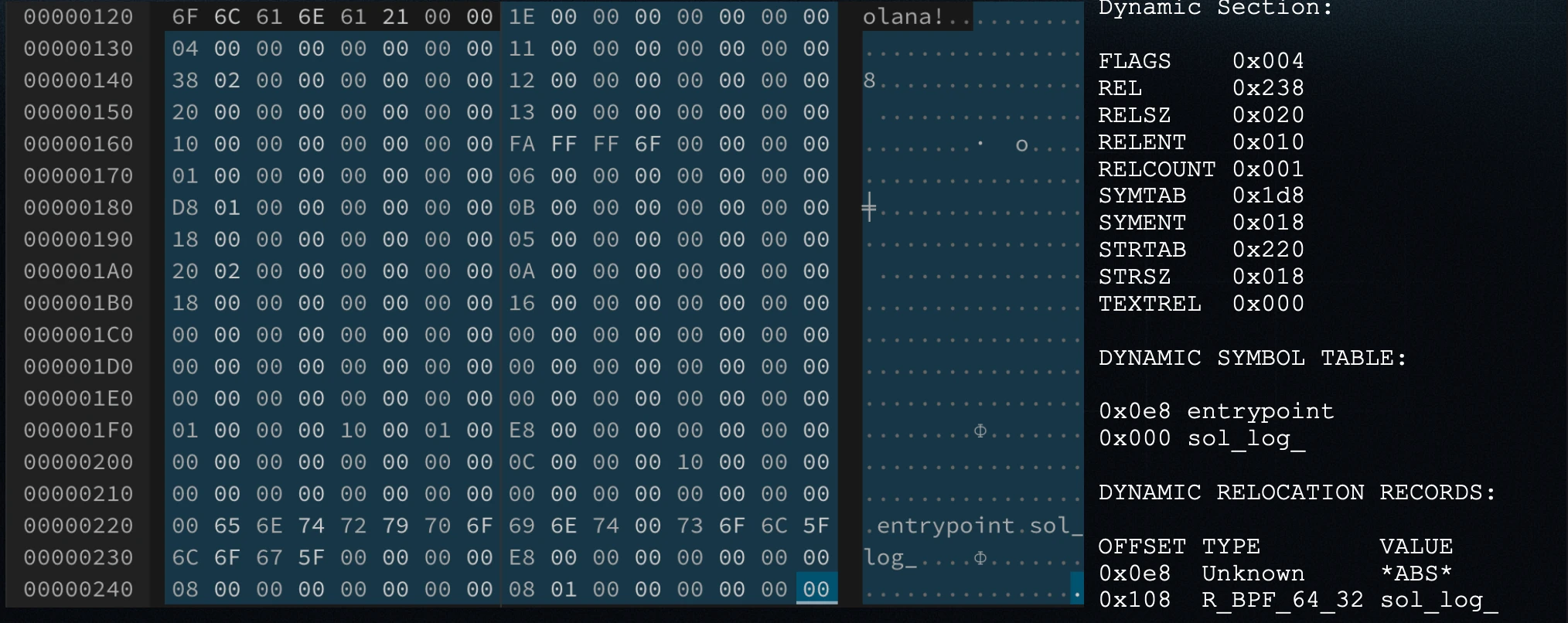

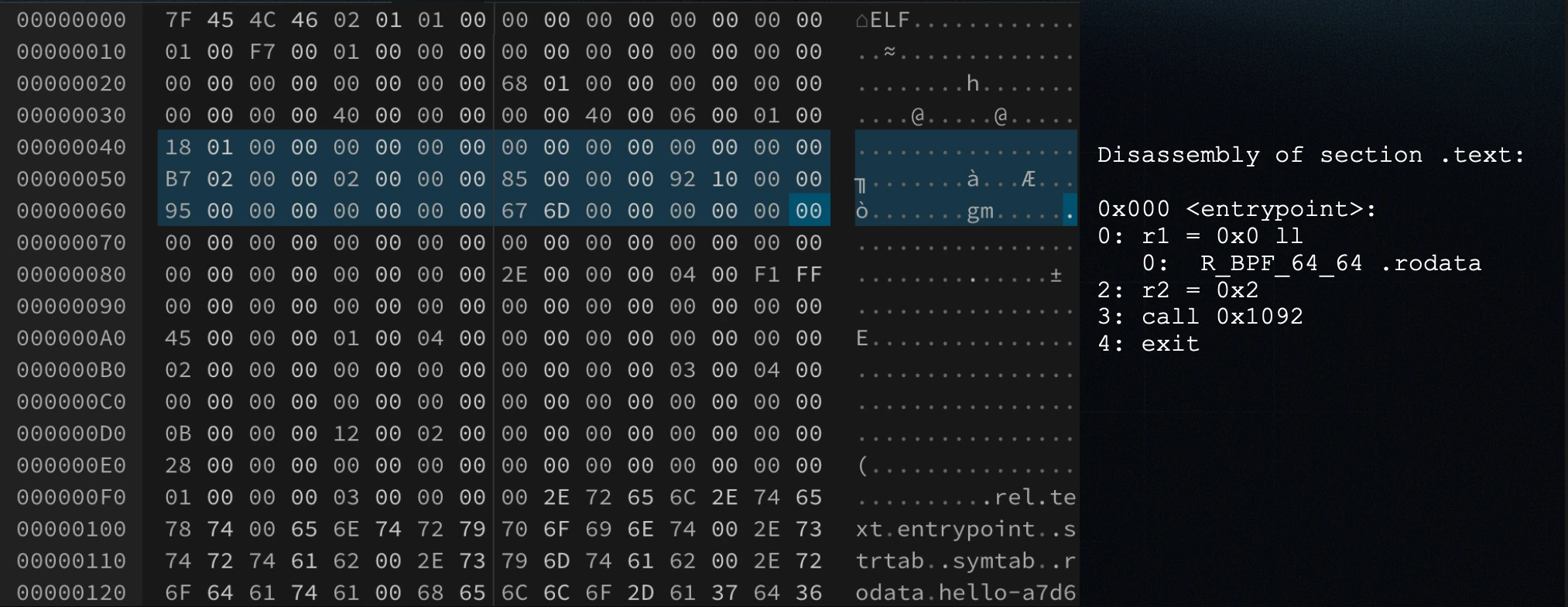

Next, there are three sections and tables that support dynamic relocation for syscalls. The Solana Virtual Machine (SVM) looks into the relocation table and symbol table to determine that a call instruction at a specific offset in the program is actually invoking sol_log_.

However, if we use static syscalls by encoding the syscall’s hash directly in the call instruction, then none of these tables are needed at all, simplifying the binary and saving space.

At the bottom of the ELF file are the section headers, which describe the offset, size and type of each section we just covered.

Now that you understand this, you could handroll a solana program using something like … Vim. But DON’T DO IT! You’d get me blocked by half of the people on Twitter haha

So how did we get here from upstream eBPF? And for that matter, what exactly is upstream eBPF?

About five years ago, Alessandro added a BPF target to the Rust compiler. This meant that kernel developers could write Rust programs, compile them to BPF using the Rust compiler, and deploy them directly into the kernel.

Adding BPF target support to the Rust compiler (by Alessandro)

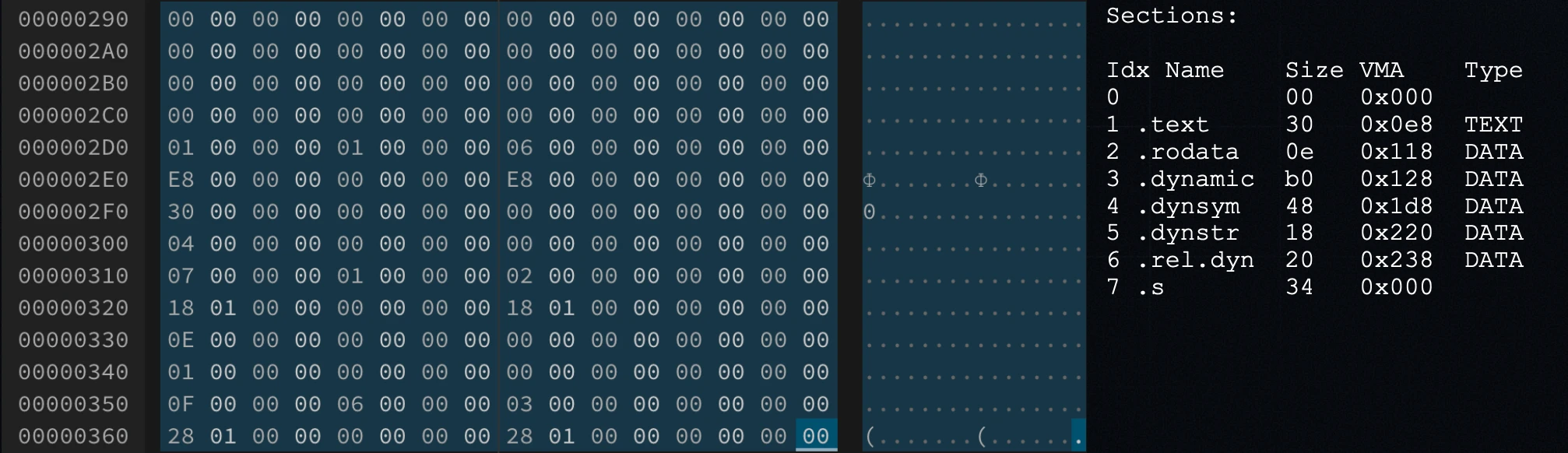

Due to Rust’s compilation model, a BPF linker is included as part of the new target support. Rust compiles each dependency or crate as a standalone compilation unit, so the linker is needed to merge all these units into a single executable (see Alessandro’s post above for more details).

Now, if we look at the bytecode generated by upstream eBPF and linked by the BPF linker, you might be surprised—or maybe not so surprised—by just how similar it is to sBPF bytecode.

Some of the major differences between upstream eBPF and sBPF are:

-

Relocation of

.rodatasymbols (line 0 in the.textdisassembly): Upstream eBPF performs relocation for.rodatasymbols. To convert this for sBPF, we need to reverse the relocation, identify which symbol is being loaded, and then encode its offset directly into the load instruction. -

Syscalls handling (line 3 in the

.textdisassembly): Upstream eBPF uses static syscalls, whereas sBPF relies on relocation-based syscalls. To support this, we add the sections and tables we discussed earlier for dynamic relocation. (Again, if we switch to static syscalls, we can skip this whole step, and it works pretty well in upstream eBPF.) -

callxencoding: In sBPF, the destination registers forcallxare encoded differently depending on the sBPF version. We need to handle these encodings correctly for each version.

At this point, generating Solana programs from upstream eBPF has become fairly straightforward. We essentially need two things: a BPF linker to compile the Rust program into a single executable, and another tool to repackage it into the bytecode format that the SVM understands.

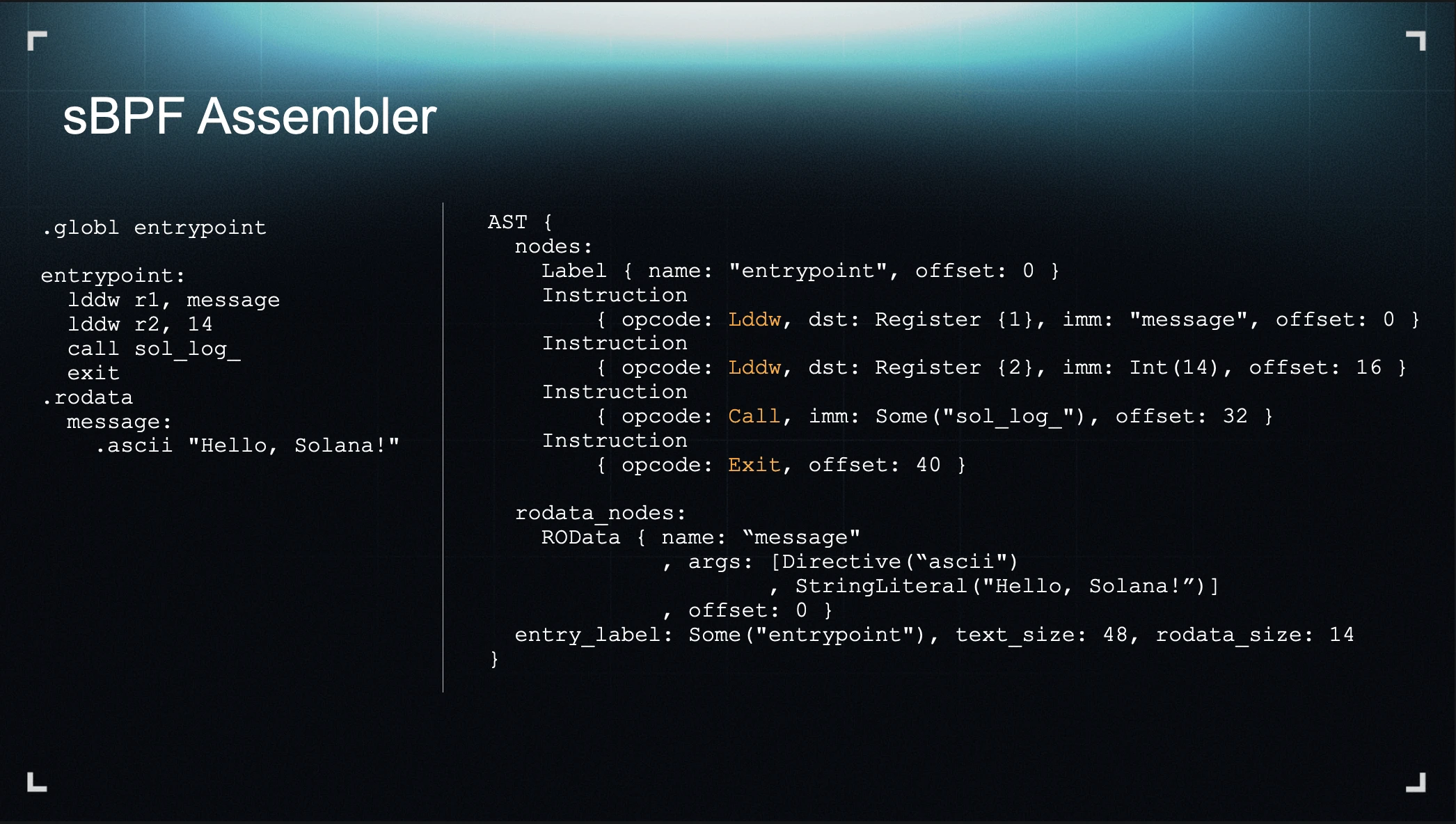

In fact, we’ve had this capability for a while. For those who have been following Blueshift, you might know about our sBPF assembler, which doesn’t depend on any LLVM toolchain. This assembler is what powers the sBPF linker.

Here’s how it works: it parses an assembly program into an abstract syntax tree (AST). The AST can calculate offsets, generate sections, encode instructions, and create relocations, essentially performing direct bytecode generation for a Solana program. The only difference between the assembler and the linker is the input type: the assembler parses a text-based assembly file, while the linker parses an object file.

If you look at the code for the sBPF linker, this is essentially all it does: it first calls the BPF linker to merge the program into a single object file, and then it takes that object file, re-parses it, and generates a Solana program.

That’s about sBPF linker!

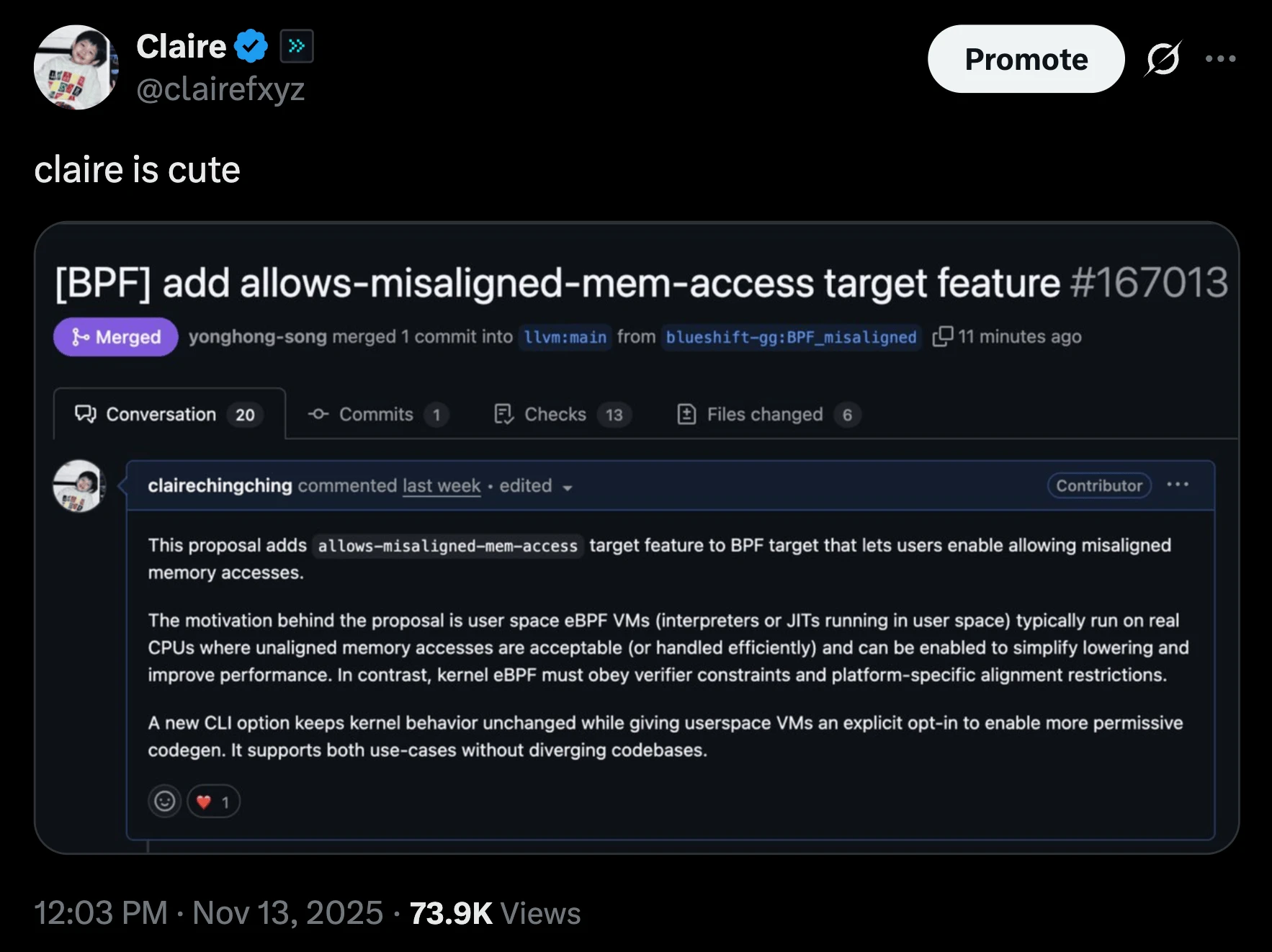

The last thing I want to mention is, now that work with upstream eBPF is possible, we should stop being a bad consumer of the technology we’re using, we should try to be a good contributor. For example, if I find something useful to the BPF target in general, we should try to upstream it so that people outside Solana can also benefit from it

To me, this is not just about credibility. From an engineering perspective, the more people use an optimization pass, the more robust it becomes. Because it gets better tested and more edge cases are discovered. The sBPF linker opens up exactly that path, enabling contributions that improve the broader ecosystem while also benefiting Solana.